In a typhoon-ravaged island in the Philippines, children are empowered to create a safe and sustainable environment.

Ivy Marie Mangadlao, Philippines

In Halian Island, a remote island community in Siargao, Southern Philippines, the concept of safety as perceived and experienced by children is very different. ‘Safety’ extends beyond physical security and protection. For them, safety also means access to education, freedom from violence, opportunities for growth, and emotional well-being. Living in an area prone to natural disasters like typhoons, these children experience challenges that shape their understanding of safety in ways that go beyond the conventional.

Beautiful but vulnerable, Halian Island is frequently threatened by severe weather events like Super Typhoon Odette (international name: Rai) which devastated the island in 2021. The effects of climate change are prevalent in the surroundings in which children grow up, influencing their daily routines, homes and schools.

My photo essay for ‘Safe’ explores the different facets of the children’s lives, following how children navigate and redefine the concept of safety within their community.

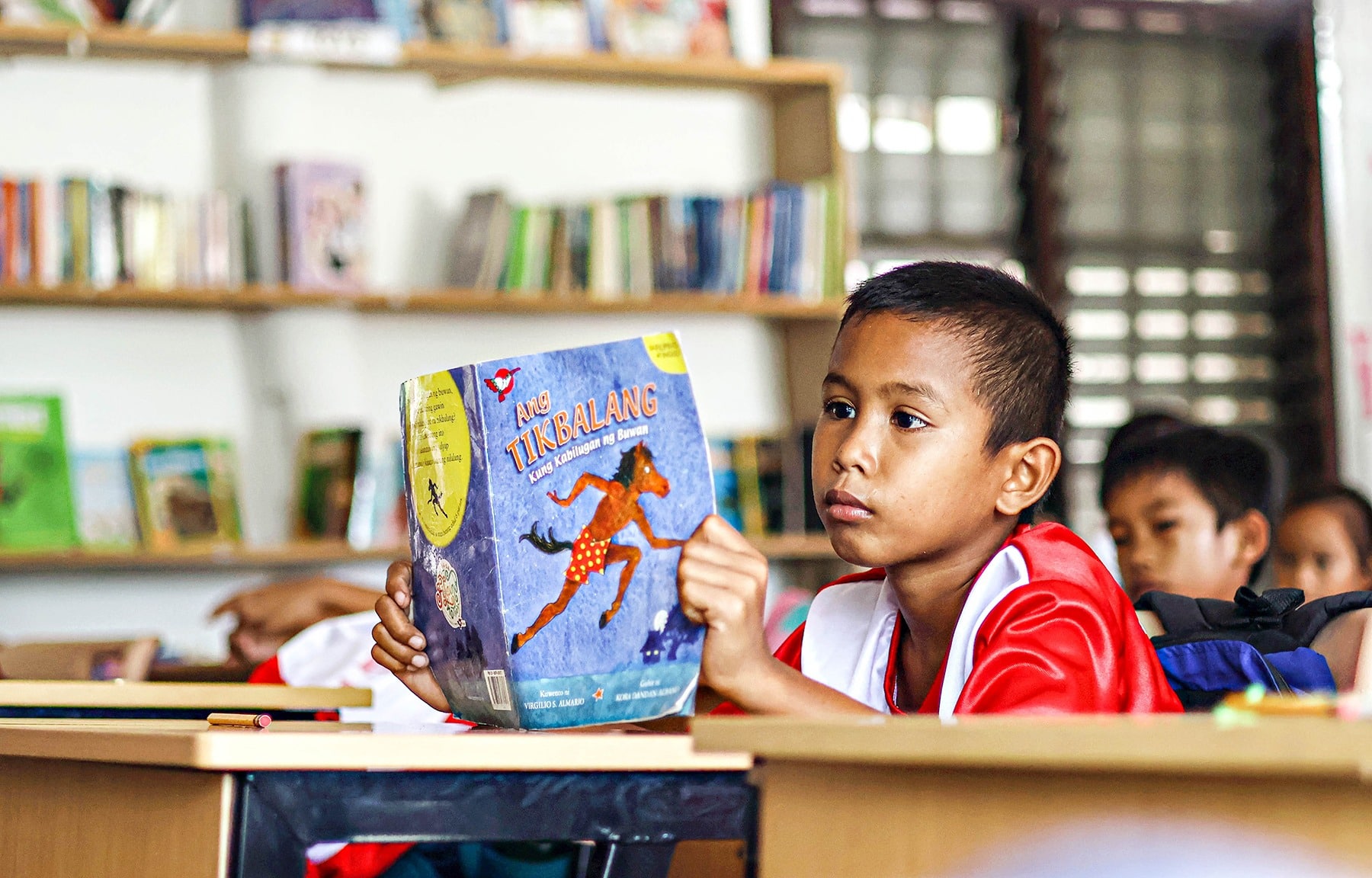

A focal point of my essay is the Seawikan Kids Patrollers, who are pictured here. They are a group of young children who participate in beach clean-ups and environmental and social activities. By their actions these kids are not only recipients of aid but also actively contribute to the creation of a more sustainable and safe environment. The group’s efforts such as cleaning up trash along the shore and educating other locals demonstrate that kids can affect positive change in spite of the challenges they encounter. Being role models in their community, the Seawikan Kids Patrollers show that safety for them, is about fostering an environment where they and others around them can thrive.

The concept of safety, as seen through the eyes of these children, also encompasses the emotional aspect—being able to express themselves, feeling supported by their families and community, and having the space to grow without fear.

My hope is that my pictures will elevate the voices of children who are frequently disregarded, or portrayed as helpless victims of their circumstances. Instead, I portray them as proactive change agents, taking charge of their environment and their futures. The images serve as a powerful reminder that children should be central to conversations on climate action, community safety, and policy development.

Safe is more than just a visual representation of childhood in Halian Island; it’s a call for action. It emphasises the need for a collective effort from families, communities, policymakers, and society at large to create spaces where children are empowered to feel, be, and stay safe—both in their physical environments and in their emotional journeys. It is a visual testament to the power and potential of young people, not as passive recipients of aid, but as leaders and active participants in building their own futures.

Siblings Ralph and Roy Pangan used to walk the shores of Halian, a remote island community in the southern Philippines, often helping their father, Rudel—known to the villagers as “Ompong”—carry his overnight catch, or simply playing by the water.

For them, like many other children on the island, this was a daily routine—until Super Typhoon Odette ravaged their island in December 2021.

The typhoon left scars on the community, bringing trauma that would take time and resources to heal. But amid the destruction, something remarkable emerged.

The disaster revealed that the children of Halian could play a role far beyond helping their parents or enjoying the island’s shores as they could become agents of change and resilience, helping to rebuild their community and protect their environment.

The Birth of the Seawikan Kids Patrollers

As the island worked to recover from the typhoon, community involvement, particularly among the children, grew. Lady Carmel Litang, a 25-year-old community leader, recalled how eager the kids were to participate in the rebuilding efforts.

“Right after the typhoon, the shore was covered in debris. We started cleaning up, and the kids just naturally joined us.”

What began as spontaneous help evolved into something more structured. By early 2024, the children were officially organized into a group called the Seawikan Kids Patrollers—a combination of “sea” and “wikan,” from pawikan, the local term for sea turtles that nest on Halian’s shores.

Every Saturday morning at 6:30 a.m., the kids patrollers gather to clean the coastline, picking up trash, segregating it, and documenting their collections.

After each cleanup, the children are treated to breakfast at the home of Jennifer Dullo, a former barangay secretary who volunteers her time to cook.

“We don’t always have funds for the meals, but generous donors help ensure the kids are fed after the cleanup,” Lady shared.

After breakfast, they sit together by the shore to talk about their feelings, their lives, and their dreams. Lady facilitates these sessions, asking the children how they’ve been coping and encouraging them to reflect on their experiences.

“These conversations help the kids process their emotions and feel connected,” Lady said. “It’s important for them to feel that they’re part of something bigger than themselves, something that’s making a difference.”

Ralph (left) and Roy (right), once boys just playing on the shore, are now active participants.

“I enjoy picking up trash,” Ralph said. “We do it so the fish don’t die from plastic, and our island stays clean.”

When asked if it’s tiring to participate in the cleanups on a Saturday, a day triditionally meant for rest after a five-day school week, Roy simply smiled.

“I love being with the other kids from Halian,” he said. “Aside from school, it’s fun to meet up with everyone. Plus, we get free breakfast after the cleanup, and I really look forward to that!”

He added that it’s not just about the food. “We also do storytelling, have conversations, and sometimes we even get to swim together after.”

Their father, Ompong, is proud of their involvement. “It was hard for the kids after the typhoon, but these activities have really helped them cope. They’re not just playing now, they’re also contributing to the community,” he said.

Keeping Children Engaged

Halian Elementary school was severely damaged by Typhoon Odette, and classes were halted for two months. During that time, the children stayed home, helping with chores or playing.

But Lady said that her fellow community leaders understood the importance of keeping them engaged, so they organized various activities to keep the children occupied.

They conducted psychosocial support programs such as storytelling, arts and crafts, sports, and more.

The school has since been rebuilt, with the addition of solar panels and news classroom to ensure sustainability in this remote area.

Alma Litang, the school’s head teacher, expressed her gratitude for the donations from different organizations.

“With the new classrooms and solar panels, we can offer a better learning environment for the children,” Alma said.

A New Generation of Leaders

Lady reflected on her own childhood in Halian, which, for her, was simpler—filled with just chores and swimming in the sea. “Back then, we didn’t have these kinds of activities. We just played all day. But now, the younger kids are taking up space, becoming proactive in ways we never were,” she said.

Though the Seawikan Kids Patrollers are small in number for now, Lady is hopeful that their impact will grow. She’s also thankful for the support of parents like Ompong, who see the value in their children’s involvement in the community.

Though the typhoon caused havoc, Lady said that opened to the reality that children in Halian, despite their young age, can truly change the narrative. “We can help build a safe environment for them by empowering them, giving them the space to lead, and involving them in the process,” she said.

Ivy Marie Mangadlao is an early career writer and photojournalist from Butuan City, Southern Philippines. Her journey in journalism began in high school, where she contributed as a campus journalist. Today, she reports on climate change, environmental issues, culture, tourism, and community-driven stories, often immersing herself in grassroots communities.

The Safe Photography Project to End Violence Against Children and Young People holds a special place in her heart. As a visual storyteller, she has witnessed the significant impact that powerful imagery can have on people’s lives. Joining this project is her way of using her skills to advocate for vulnerable children and young people. She believes in creating a world where they can grow up free from violence and fear. Through this platform, she aims to shed light on their stories, raise awareness, and inspire change, ensuring that every child can live in safety and dignity.